VASO KATRAKI: HURTFUL BODIES

Curated by Alia Tsagkari

Photo credit: Odysseas Vaharidis, courtesy of Roma Gallery

VASO KATRAKI: HURTFUL BODIES

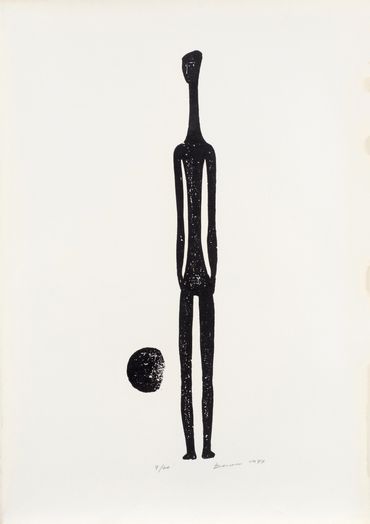

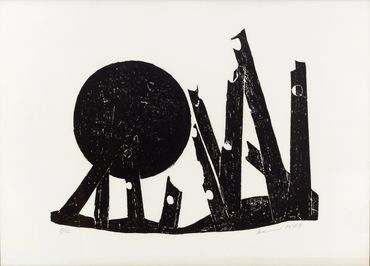

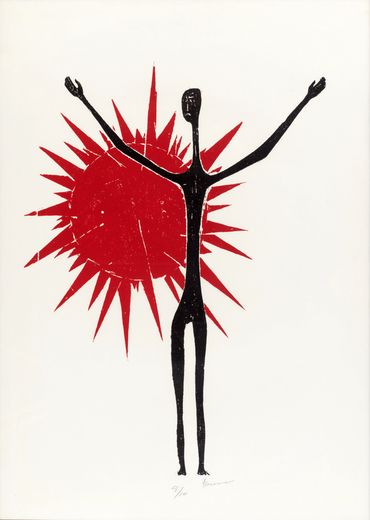

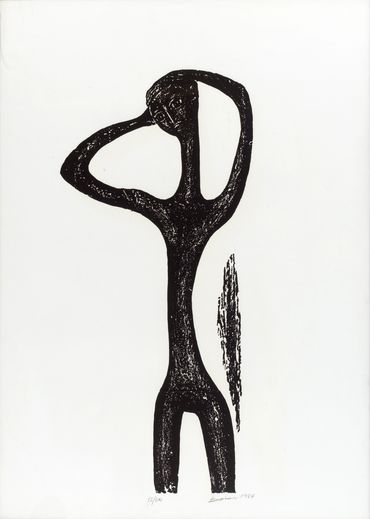

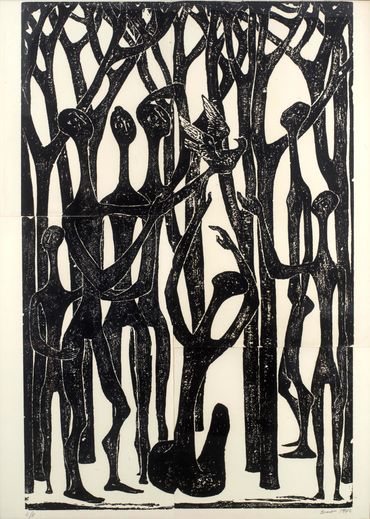

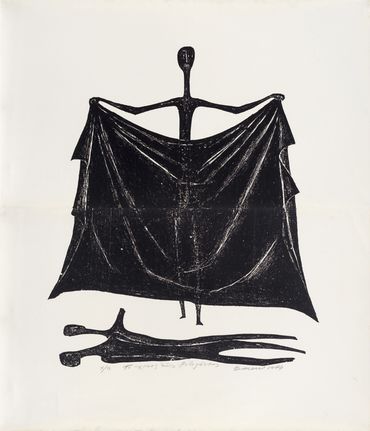

In the late works of Vaso Katraki, the human body is not merely an object of representation but an ideological and formal construct that reconfigures the anthropomorphic myth. Brimming with preclassical references—Cycladic, Archaic, and Geometric—the elongated figures, with their attenuated necks and limbs, operate as a rupture within established taxonomic systems, destabilising the boundaries between the ‘civilised’ and the ‘savage’ body. In stark opposition to sensory indolence and easy-to-digest reception, these bodies are hurtful, unyielding, and rigid. They retain the rawness and starkness of the sandstone in which they are engraved and dominate in an uninterrupted spatial field of off-white cotton paper. Depth is negated; illusionistic space is irrevocably shattered. There is no open window to the landscape, no point of escape from the body's sovereignty.

Dominant and imposing, these bodies require no interpolated sensuality. They are stripped, particularly in her late work, of gendered and racial features, transfiguring into elegiac forms—mournful and heroic. Yet, the ungendered nude remains resolutely exposed, engraved as a hurtful corporeality—rigid and intense—bearing the scars of violence and physical endurance of both the representation and the artist herself. The decisive gestural force of the engraving amplifies their impact. The materiality of the sandstone, the abrasiveness of the slash, and the deformation of the figures transcend conventional art hierarchies, securing Katraki a distinct position within the global history of engraving.

By the mid-1950s, her transition from the established technique of woodcut to engraving on sandstone marked a decisive turning point in her artistic practice. As Yannis Bolis astutely observes, this shift expanded both the expressive potential and the scale of her works, igniting new formal concerns. Katraki’s pioneering choice of sandstone over the traditionally used limestone was by no means incidental. As a sedimentary rock composed of compacted quartz grains, sandstone is rough, porous, and brittle. Its uneven erosion and limited capacity to retain ink "paved the way for large forms and broad, free gestures." Simultaneously, it’s harder surface, which necessitates sculptural tools and techniques—such as the mallet and chisel—dictates the elimination of redundant detail while enabling monumentality, leading to an intensified simplification and schematisation of the forms. The monumental presence of her dark figures, the emphasis the volumes through slashes, and their predominantly vertical arrangement evoke a preclassical iconographic type reminiscent of the black-figure ceramics of the Geometric and Archaic periods.

Echoing the increasingly pronounced contours of preclassical art, Katraki’s engravings establish the human body as the thematic nucleus of her oeuvre. Between 1967 and 1968, the sharply defined human and animal figures she drawn in black marker on smooth pebbles served both as a means of processing her exile on Gyaros following the imposition of the Greek Military Junta on 21 April 1967 and as a crystallisation of her robust contours. These contours would come to dominate her rendering of the human form upon her return from exile, where the unmediated exposure to violence and deteriorating health conditions cemented a sombre reality and the prevalence of hurtful bodies. In the wake of both political upheaval and formal experimentation, Katraki’s engraving language approximates more the handling of the human body in works of preclassical Greek cultures, such as Cycladic figurines, the black-figure ceramics of the Geometric and Archaic periods, and Archaic sculpture.

Indeed, the affinities between the human bodies in Katraki’s engravings and the archaic forms of the prehistoric Aegean in the third millennium BCE were highlighted, at least curatorially, in a landmark 2010 exhibition at the Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens. In the exhibition catalogue, Katraki’s work was positioned within the visual explorations of modernist movements, reflecting a broader turn towards archaic expressivity and the structures of non-Western civilisations. However, any reference to the concept of primitivism was omitted. Primitivism remains a contentious chapter in modernism, often approached by scholars through the safety of paraphrase and cherished interpretative schemes. A consequence of this is the neglect of its radical reappropriations from the 1960s onwards—reappropriations within which Katraki’s work is situated.

Primitivism, understood as the Western reception and appropriation of forms and practices from racial and cultural otherness, offered European modernist artists an alternative perception of the past, one unburdened by Western epistemological constructs. Instead of the neoclassical continuity championed by academic tradition, primitivism proposed an imagined, authentic, prehistoric world characterised by instinctive creativity and the untamed expression of a pre-rational, pre-modern consciousness. This perspective facilitated an absolute rupture from the past and a violent severance from tradition, principles that the European avant-garde of the early twentieth century actively promoted. Through this aestheticised view of primitivism, preclassical artefacts from non-Western cultures became iconographic models for an abstracted and reductive approach to form. Soon, to the so-called ‘primitive’ artefacts of autochthonous peoples from Africa and Oceania were added the archaeological finds of preclassical Greek cultures, a connection that gained traction—particularly in France—through reviews such as Cahiers d’Art and Documents. A telling example is one of the earliest critical assessments of Giacometti’s sculpture, in which Christian Zervos highlights its affinity with Cycladic art as a form of primitive sculpture. However, Giacometti’s primitivism, like that of most modernists—Picasso, Brancusi, Modigliani, and Moore, to name but a few—is purely morphological and thus gutless, if not outright colonialist.

Within these historical and methodological frameworks, this curatorial approach to Katraki’s late work foregrounds the reappropriation, whether conscious or unconscious, of primitivism and its rendering of the human form transferred on paper as primordial, unrefined, and hurtful. In particular, within the critical reception of modernism and its cultural products, this analysis aligns ideologically with Rosalind Krauss’s concept of a ‘hard’, non-aestheticised primitivism, yet diverges in two key respects. Firstly, in its temporal focus on contemporary Greek art rather than European modernism, and secondly, in its articulation through corporeal representations that directly reference the ‘primitive’ Greek civilisations with which Katraki was profoundly and experientially familiar. At this juncture, it is imperative to emphasise that the primitivism of Katraki’s figures is not haunted by the spectre of colonialism that weighs heavily upon European modernism.

On a formal level, the verticality and planar modelling of the human figures, bearing strong affinities with prehistoric artefacts, do not merely replicate earlier models as an exoticised visual idiom. Instead, they subvert the very process of primitivisation, dismantling the binary opposition between the "civilised" and the "savage" body. Dominant and self-referential, Katraki’s figures do not belong to a fetishised imaginary iconography of the primitive but emerge as autonomous, historically and materially inscribed entities. In stark contrast to the shortcomings of the European avant-garde, which frequently imbued "wild" bodies with a crude aesthetic that served the ideological constructs of the Western gaze, Katraki inscribes the body onto matter in a manner that integrates historical memory and reveals trauma—both physical and psychological—as an inherent condition of human existence. More specifically, the austere, Doric plasticity of her figures, stripped of idealisation, reinstates the "primitive" iconography as an expression of cultural alterity that threatens to rupture the "noble simplicity" and "quiet grandeur" of the Neoclassical ideal.

From this perspective, Katraki’s elongated, preclassical forms do not function as nostalgic references to prehistoric Greek cultures but as a radical return to primitive corporeality. This return is not an act of negation but of revival, achieved through a tactile engagement with materiality and an immersive sensory experience. After all, Katraki’s figures do not belong to the realm of "polite classicism" nor to the raw, unformed materiality often ascribed to "primitive" cultures. These bodies are neither "wild" nor "civilised" in the colonial sense, but autonomous, archetypal, and intrinsically bound to the memory of a native antiquarian tradition within which the artist lived and worked.

At the same time, in Katraki’s late work, as bodies shed racial and gendered identifiers, their nudity acquires a paradoxical fusion of severity and allure. Far from passive objects of visual consumption, these bodies emerge as present and confrontational. Their threatening self-referentiality is further accentuated by the rough materiality of stone and the robust corporeality of form, which re-inscribes trauma onto the human figure, transmuting the manual labour of engraving into an act of resistance. In this way, Katraki’s handling of sandstone activates her own bodily presence, deconstructing the "noble" detachment of traditional artistic expression and foregrounding the wounded body as a site of desire, transformation, and danger.

Katraki’s late work redefines the primitive not as an aesthetic pursuit or formal reference but as a lived, embodied experience indelibly inscribed in the hurtful imprints of the human form. Through her persistent elevation of corporeality as a site of historical memory and resistance, the primitivism of her figures is not an anachronistic recourse to archaic models but a radical instrument for confronting modern Greek history.

Alia Tsagkari

Athens, 10 March 2025

VASO KATRAKI

Vaso Katraki was born in 1914 in Aitoliko, a small fishing town by the Messolonghi lagoon.She studied painting and engraving at the Athens School of Fine Arts (1936-1940) under the tutelage of Kostis Parthenis and Yannis Kefallinos, respectively. She specialized in wood engraving, copper engraving, lithography, and typography. She graduated with a scholarship, an award, and two distinctions in engraving. With the outbreak of the war, the ASFA's Engraving Workshop actively participated in the effort to boost morale by creating posters, among which Katraki’s Woman Knitting was selected.

In 1947, she participated in the International Cairo Exhibition (Cairo) and Grekisk Konst (Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm). In 1949, she became a founding member of the artistic "Stathmi" and exhibited at Zappeion (1950). In 1952, she showcased her wood engravings and woodcuts at the Panhellenic Exhibition at Zappeion (Athens). This was followed by the exhibitions Mostra di Pittura Hellenica Contemporanea (National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome, 1953) and the exhibition of Greek engravers (Geneva, 1954). In 1955, she began working with sandstone and participated in the exhibitions La Grèce Vivante (Museum of Art and History, Geneva, 1955) and Nutida Grekisk Konst (Gothenburg, 1955).

In 1955, she held her first solo exhibition at the "Zachariou" gallery (Athens). This was followed by the International Woodcut Exhibition “Xylon” (Zurich & Ljubljana, 1956), the São Paulo Biennial (1957), and the Biennale of Mediterranean Countries (Alexandria, 1957), where she was awarded the first prize for engraving in 1958. That same year, she received the first prize at the International Exhibition of Drawing and Printmaking “Bianco e Nero” at Lugano (1958). In 1959, she exhibited at the "Zygos" gallery (Athens), and participated in the Greek Engraving Exhibition (Pushkin Museum, Moscow, 1959).

From 1960, she regularly participated in the Tokyo Engraving Biennale. She took part in exhibitions such as Greek Art (Bucharest, 1962) and Peace and Life (gallery "Zygos", Athens, 1962). From 1963, horses became a central theme in her work. In 1964, she held a solo exhibition in Beijing and participated in the group exhibitions Greek Art(Buenos Aires) and Greek and American Engraving (Hellenic-American Union, Athens). In 1966, she was honoured with the international "Tamarind" lithography award at the Venice Biennale, while in 1967 she exhibited at the Athens Art Gallery – Hilton and the Greek Artexhibition (Montreal). Following the imposition of the dictatorship, she was arrested and exiled (1967-68). Upon her return from exile, she exhibited at the "Argo" gallery (Nicosia, 1971), the Capri Biennale of Engraving (1969), the Athens Art Gallery – Hilton (1971), the galleries "Nees Morfes" (1972) and "Ora" (1973), and the Greek Art Exhibition (Madrid, 1972).

In 1976, she received the first prize at the Intergrafik International Exhibition of Graphic Arts (East Germany), and participated in exhibitions at the Museum am Ostwall (Dortmund), the galleries "Argo" and "Polyplano" (Athens), and the International Exhibition of Contemporary Art (Basel). In 1977, she took part in the exhibitions Greek Engraving (gallery "Nees Morfes", Athens), Balkan Painting(Bucharest), and Systowa Wisproczesner Sztuki Greckies (Warsaw). In 1978, she participated at the exhibition Modern Greek Painters and Engravers(Nicosia), and presented works at the International Exhibition of Contemporary Art (Basel) with the "Polyplano" gallery and at the Paul Facchetti gallery (Paris). In 1979, she participated in the Baden-Baden Biennale and the Contemporary Greek Painters and Print Makers exhibition (National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin).

On February 20, 1980, the National Gallery and Alexander Soutzos Museum inaugurated the major retrospective exhibition Vaso Katraki. Engravings, 1940-1980, which honoured her work. Throughout that decade, Katraki's presence in group exhibitions in Greece and abroad continued unabated.

In 1982, she participated in Europalia (Brussels), the exhibition Glances at Greece (Athens Art Gallery), and the Engraving Exhibition of 49 Greek Artists (Cultural Center of the Municipality of Athens). In 1983, she presented at Modern Greek Prints (London). In 1984, she held a solo exhibition at the "Aixoni" gallery and designed an original composition for a stamp for the Greek Post commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Polytechnic uprising.

In 1985, the engraver participated in Memories – Reconfigurations – Searches (Athens Conservatory) and in 1986 she presented the Elegies series at the "Athina" gallery. In 1987, she co-founded the Association of Greek Engravers and presented works at the exhibitions Engravings in the War, the Occupation and the Resistance("Hyakinthos" gallery), The Workshop of Kefallinos("Pleiades"gallery), Peace (Greek Committee for International Peace), Panhellenic Exhibition (Piraeus Port Organization), Works–Events (Kostis Palamas Building, University of Athens). She also created a poster for the “5th Human Shield of Peace around the Acropolis”. In 1988, she participated in the exhibitions Greek Post-War Engraving (National Gallery), Wspotczesna Graffika Grecko (National Museum, Warsaw), and the First Mediterranean Biennale of Engraving (Mirabello, Crete) etc.

On December 27, 1988, Katraki passed away at the age of 74.

Vaso Katraki was born in 1914 in Aitoliko, a small fishing town by the Messolonghi lagoon.She studied painting and engraving at the Athens School of Fine Arts (1936-1940) under the tutelage of Kostis Parthenis and Yannis Kefallinos, respectively. She specialized in wood engraving, copper engraving, lithography, and typography. She graduated with a scholarship, an award, and two distinctions in engraving. With the outbreak of the war, the ASFA's Engraving Workshop actively participated in the effort to boost morale by creating posters, among which Katraki’s Woman Knitting was selected.

In 1947, she participated in the International Cairo Exhibition (Cairo) and Grekisk Konst (Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, Stockholm). In 1949, she became a founding member of the artistic "Stathmi" and exhibited at Zappeion (1950). In 1952, she showcased her wood engravings and woodcuts at the Panhellenic Exhibition at Zappeion (Athens). This was followed by the exhibitions Mostra di Pittura Hellenica Contemporanea (National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome, 1953) and the exhibition of Greek engravers (Geneva, 1954). In 1955, she began working with sandstone and participated in the exhibitions La Grèce Vivante (Museum of Art and History, Geneva, 1955) and Nutida Grekisk Konst (Gothenburg, 1955).

In 1955, she held her first solo exhibition at the "Zachariou" gallery (Athens). This was followed by the International Woodcut Exhibition “Xylon” (Zurich & Ljubljana, 1956), the São Paulo Biennial (1957), and the Biennale of Mediterranean Countries (Alexandria, 1957), where she was awarded the first prize for engraving in 1958. That same year, she received the first prize at the International Exhibition of Drawing and Printmaking “Bianco e Nero” at Lugano (1958). In 1959, she exhibited at the "Zygos" gallery (Athens), and participated in the Greek Engraving Exhibition (Pushkin Museum, Moscow, 1959).

From 1960, she regularly participated in the Tokyo Engraving Biennale. She took part in exhibitions such as Greek Art (Bucharest, 1962) and Peace and Life (gallery "Zygos", Athens, 1962). From 1963, horses became a central theme in her work. In 1964, she held a solo exhibition in Beijing and participated in the group exhibitions Greek Art(Buenos Aires) and Greek and American Engraving (Hellenic-American Union, Athens). In 1966, she was honoured with the international "Tamarind" lithography award at the Venice Biennale, while in 1967 she exhibited at the Athens Art Gallery – Hilton and the Greek Artexhibition (Montreal). Following the imposition of the dictatorship, she was arrested and exiled (1967-68). Upon her return from exile, she exhibited at the "Argo" gallery (Nicosia, 1971), the Capri Biennale of Engraving (1969), the Athens Art Gallery – Hilton (1971), the galleries "Nees Morfes" (1972) and "Ora" (1973), and the Greek Art Exhibition (Madrid, 1972).

In 1976, she received the first prize at the Intergrafik International Exhibition of Graphic Arts (East Germany), and participated in exhibitions at the Museum am Ostwall (Dortmund), the galleries "Argo" and "Polyplano" (Athens), and the International Exhibition of Contemporary Art (Basel). In 1977, she took part in the exhibitions Greek Engraving (gallery "Nees Morfes", Athens), Balkan Painting(Bucharest), and Systowa Wisproczesner Sztuki Greckies (Warsaw). In 1978, she participated at the exhibition Modern Greek Painters and Engravers(Nicosia), and presented works at the International Exhibition of Contemporary Art (Basel) with the "Polyplano" gallery and at the Paul Facchetti gallery (Paris). In 1979, she participated in the Baden-Baden Biennale and the Contemporary Greek Painters and Print Makers exhibition (National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin).

On February 20, 1980, the National Gallery and Alexander Soutzos Museum inaugurated the major retrospective exhibition Vaso Katraki. Engravings, 1940-1980, which honoured her work. Throughout that decade, Katraki's presence in group exhibitions in Greece and abroad continued unabated.

In 1982, she participated in Europalia (Brussels), the exhibition Glances at Greece (Athens Art Gallery), and the Engraving Exhibition of 49 Greek Artists (Cultural Center of the Municipality of Athens). In 1983, she presented at Modern Greek Prints (London). In 1984, she held a solo exhibition at the "Aixoni" gallery and designed an original composition for a stamp for the Greek Post commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Polytechnic uprising.

In 1985, the engraver participated in Memories – Reconfigurations – Searches (Athens Conservatory) and in 1986 she presented the Elegies series at the "Athina" gallery. In 1987, she co-founded the Association of Greek Engravers and presented works at the exhibitions Engravings in the War, the Occupation and the Resistance("Hyakinthos" gallery), The Workshop of Kefallinos("Pleiades"gallery), Peace (Greek Committee for International Peace), Panhellenic Exhibition (Piraeus Port Organization), Works–Events (Kostis Palamas Building, University of Athens). She also created a poster for the “5th Human Shield of Peace around the Acropolis”. In 1988, she participated in the exhibitions Greek Post-War Engraving (National Gallery), Wspotczesna Graffika Grecko (National Museum, Warsaw), and the First Mediterranean Biennale of Engraving (Mirabello, Crete) etc.

On December 27, 1988, Katraki passed away at the age of 74.

Copyright © 2025 Alia Tsagkari - All Rights Reserved.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.